Birmingham 1921: Best Speech by the “Worst?” President, (Warren G. Harding)

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: American Empire, Black History, Bobby's World, Church History, Contemporary Ethics, Culture, Martin Luther King, Politics, Race Relations, Unity“Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue, so that you may live and occupy the land that the LORD your God is giving you” (Deuteronomy 16.20, NRSV).

Prelude

In November 1920, Warren G. Harding defeated Democrat James M. Cox to win the twenty-ninth presidency of the United States. It was not called a landslide but “an earthquake.” The progressive Republican Harding had won every state except eleven, all eleven of those in the Deep South. In fact the election of Harding followed the exact same lines as the election of Abraham Lincoln a couple generations before. There was a reason for this.

I have been fascinated with the 1920s for many years. It was a decade of profound importance for my religious tribe, the USA, and the world. It was a decade of parties, optimism, the Harlem Renaissance, virulent racism, and unbridled violence. Today I want to remember an event that took place in 101 years ago this month on October 26, 1921 in my home state of Alabama in the city of Birmingham: The Best Speech by the “Worst?” President.

Warren Gamaliel Harding (1865-1923): The Best of the Worst Presidents

Warren G. Harding, the 29th President of the United States, came from an abolitionist family in Ohio. I became interested in Harding in 2010 when I read a book on the 1920 election by David Pietrusza, 1920, The Year of Six Presidents. In many ways 1920 has many eerie similarities to the 2020 election. It was filled with conspiracy theories, rumors, intrigue, and lies. Hiram Johnson even ran on a “America First” slogan! Former President Theodore Roosevelt was a front runner with solid progressive Republican credentials. He unexpectedly died and the Republican Party was desperate to find a candidate.

Through Pietrusza, I learned of all the rumors surrounding Warren G. Harding. From his childhood, Harding had been called the inflammatory racial slur (the “N” word). His father-in-law also believed he was not “white” and practically disowned his daughter for marrying him. When he ran for President, a Professor of History at Wooster College, William Chancellor, went on the war path against Harding publishing several documents proclaiming “Warren Gamaliel Harding Is Not a White Man.” Chancellor claimed he had evidence that Harding’s great-grandmother was black therefore he was “one-eighth” black. In the lingo of the day, an “Octoroon.” But the “One-Drop Rule” would make Harding black. In the 1920s and decades following tens of thousands of “black” Americans “passed” as white for reasons the reasons that produced the animosity toward Harding (see the story of Gail Lukasik who discovered her mother was “black” doing DNA research on her family, “My Mother Spent her Life Passing. Discovering Her Secret Changed My View“). Harding, actually never responded to the rumors. But in 2015, DNA tests on his grandchildren revealed African heritage in Harding was “not likely.”

Southern Democrats violently opposed Warren G. Harding, with or without, rumors of his great-grandmother. His record on progressive Republican values (of the day) was a clear and present danger to them. Arkansas Governor Charles H. Brough publicly railed against Harding for urging black’s to vote.

“This, of course, strikes at the very heart of white supremacy … The presidential election means everything in the south and I urge you … to explain to your people [i.e. in Ohio] just what Senator Harding’s triumph would mean in robbing the south of her most cherished birth-right, Anglo-Saxon supremacy.” (cited in Pietrusza, p. 366).

But Harding ran on a progressive Republican ticket with Calvin Coolidge. He won in a landslide victory with the massive turn out of women voters of 1920 (their first Presidential election). Harding had sought the “black vote” too.

As a Senator he had supported the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill introduced by Leonidas Dyer of Missouri in the wake of the riots in East St. Louis in 1918. Harding, as President, would introduce and ask the Republican controlled Congress to pass the Bill. Harding released a statement. “If the Senate of the United States passes the Dyer anti-lynching bill, it wont be in the White House three minutes before I’ll sign it and having signed it, enforce it.” But the bill died in the Senate by means of a southern filibusterer in 1922. As a candidate Harding publicly supported the Bill. Recently Congress finally passed such legislation but was opposed by Republican Rand Paul. When Harding was elected, he reversed the policy of the virulent racist Woodrow Wilson of expunging African Americans from federal appointments and filled a number of positions.

Early in Harding’s Administration, the Tulsa Race Massacre took place. Unbridled carnage was unleashed upon “Black Wall Street” from May 32 to June 1, 1921. Thirty-five city blocks looked as desolate as a lunar landscape, hundreds were murdered, and thousands dislocated. Unknown to almost every Republican (and likely most Americans), a week after Tulsa, President Harding journeyed to Pennsylvania to do the Commencement address at the oldest degree granting Black college in America, Lincoln University. In stunning contrast to a Republican 100 years later who went to Tulsa itself, he addressed the students about the status of America. First thing he did was acknowledge, and thank, 367,000 black American “patriots” who fought in World War I. He addressed the students as “my fellow countrymen.” And at that black university he made a public statement on Tulsa, a prayer. “God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it.” And shocking to many, he then went down the line and individually congratulated and shook the hand of every one of them. But he was not done.

Trip to Birmingham, Alabama October 1921

President Harding’s trip to Lincoln University is virtually forgotten even by professional historians. When they write about Presidents that have visited historically black colleges and universities, it is not mentioned. But he was the first and the occasion was significant.

Five months after Tulsa and addressing the students at Lincoln University, Harding would become the first sitting President to travel to the Deep South since the Civil War. He would travel to non-other than Birmingham Alabama for its “semi-centennial.” The trip was a favor for his old Democrat Senator friend, Oscar Underwood. Birmingham was the “Magic City.” It did not even exist in the Civil War. It was the icon of what could be in the “New South.” The President coming to the party brought out well over 150,000 people.

When he arrived via train to Birmingham he received a 21-gun salute and rode in a Preston Motor Corporation automobile manufactured in the Magic City (I never heard of them until I began investigating this history years ago). Harding rode in the car to the hotel with his wife Florence, former Mayor John B. Wood, and an African American named Frank McQueen. Perhaps a harbinger of what was to come. In the heart of the former Confederacy, a President would call for full participatory citizenship for African-Americans.

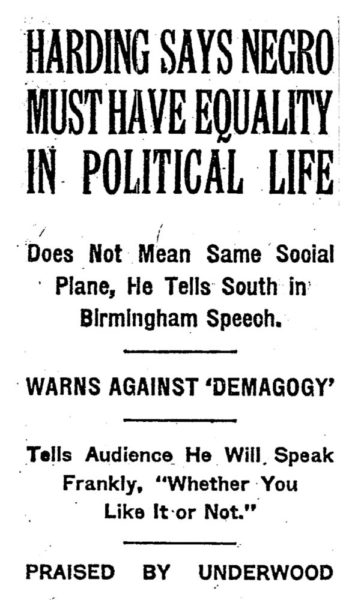

Speech to 150,000 in Woodrow Wilson Park

Some say as many as 170,000 were gathered in the recently renamed Woodrow Wilson Park on October 26 for the President arriving for the “Semicentennial of the Founding of the City of Birmingham, Alabama.” Both white and black came from all over Alabama and surrounding states. The crowds were separated by a barrier to ensure there was no “race mixing.” All were eager to have the President in the Magic City. Harding appeared before the massive crowd at 11:30. After Alabama Governor Thomas Kilby and Birmingham Mayor Nathanial Bartlett shared some words with the crowd, Harding stood. What he said that day is something I never heard a word about until a decade ago. His words that day were like an explosion. Harding became the first President to address the matter of Civil Rights and he did it in Alabama.

Warren Harding was no Barack Obama or Ronald Reagan when it came to public speaking. But what he did say revealed a man who was a student, who had digested sources and had reflected on the issues of the day.

Harding opens by reminiscing on how the South had responded in moments of crises in the past. How industry had sort of just “magically” appeared where there was none previously (Birmingham the prime example of “Magic”). Then he makes a statement that foreshadows concerns he will address in the speech. “I have many times wished that there might be a wider appreciation of the energy, resourcefulness, and genius for industrial development which the people of the South demonstrated during that [Civil] war.” Harding voices the belief that such energy devoted “would present a picture of opening opportunity and widening horizon whose contemplation would challenge every remaining vestige of prejudice.” Harding reviews such advances as the telegraph, telephone, automobiles and marvels that were put to service in the World War. Harding knows where he is and has been quite tactful. He wants to be heard.

Then in paragraph ten, Harding remains “presidential” and diplomatic, but turns reflective and challenging. He wants Birmingham, and the South, to see that a new world is emerging. He said to the 150,000+ people, “there never was a time when we needed so much to study our past and, in the light of its lessons, give earnest thought to the tomorrows.” He said, “it may be proper to suggest a few thoughts regarding the critical times which are faced by our country.” Alabama was about to get more than it bargained for with the first Presidential trip to the Deep South since the Civil War.

President Harding reveals himself to be surprisingly perceptive of cultural trends and pressures in the the USA and even the world. He believed that the World War was producing incredible changes that America must face honestly. Second, and I personally was surprised to see him recognize this, change has been brought about “by a great migration of colored people to the North and West.” He states forthrightly “the World War brought us to full recognition that the race problem is national rather than merely sectional.” Hundreds of thousands of black soldiers fought honorably in Europe and “as patriotically as did the white men” and they “experienced life of countries where their color aroused less antagonism” than in the States. The War had produced a sense of pride and “citizenship” in Black America that simply could not be denied nor ignored.

Suddenly, Harding brings up the well known race apologist Lothrop Stoddard and his book, The Rising Tide of Color. Stoddard was a white supremacist who believed (as did W. E. B. DuBois) that race and European white hegemony would be the defining issue of the 20th century. England and the USA was called to action by Stoddard. As the Governor began to squirm, Harding rejected Stoddard and endorsed an article in the Edinburgh Review (a semi-scholarly literary and politically progressive quarterly journal published in England). He said, “we must realize that our race problem here in the United States is only a phase of a race issue that the whole world confronts.”

Because of the progress in the world. Because of the undeniable patriotic service of black men in the war. Because of the changing demographics in the USA. Harding said something that white Alabama did not want to hear from a President on the anniversary of their city. “We shall find an adjustment of relations between the two races, in which both can enjoy FULL CITIZENSHIP, the full measure of usefulness to the country and of opportunity for themselves … regardless of race or color.”

The hundred plus thousand white Southerners gathered in Woodrow Wilson Park sat in stunned silence. On the other side of the barrier, tens of thousands of Black Americans erupted.

After a few moments, Harding decided to clarify. At this distance we do not know if this was a political clarification or something he genuinely believed. But it is clear Harding knew Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey as well as W. E. B. DuBois. So he says, he does not mean “social equality” which in the South meant, at bottom, inter-racial marriages (which is what Harding meant as is clear in the speech). But then Harding explains what he does mean by “equality.” The South understood it to be nothing less than “social equality.”

Political Equality

Harding proceeded to lay out “equality.” Harding said that equality demanded a “political aspect.” Black men had earned the right for Black America to the ballot. “I would say let the black men vote when he is fit to vote: prohibit the white man voting when he is unfit to vote.” Black and white should be treated equally at the ballot box.

Educational Equality

Harding was a believer in education for lifting all humanity to a higher plane. He says, indeed, insists upon it for African Americans. “I would insist upon equal educational opportunity for both.” Harding noted this does not mean that ever single person would end up with the same education. He points out that plenty of white people do not have the same educational background. But that educational opportunities are to be available for those seeking them and have the capacity to pursue even higher education and through it higher quality of life. Again, equal access to education, raises the specter of white girls dating black men. So in the middle of a paragraph on equal education, Harding says again remembering where he was, says “racial amalgamation there cannot be.” But he issues this admonition to the massive crowd.

“I can say to you people of the South, both white and black, that the time has passed when you are entitled to assume that this problem of races is peculiarly and particularly your problem. More and more it is becoming a problem of the North: more and more it is the problem of Africa, of South America, of the Pacific, of the South Seas, of the world. It is the problem of democracy everywhere, if we mean the things we say about democracy as the ideal political state. Coming as Americans do from many origins of race, tradition, language, color, institutions, heredity; engaged as we are in the huge effort to work an honorable destiny from so many different elements.”

Harding’s message was, because of the times, we must change. In fact, as he noted, it is “passed” time.

Harding believed “it is a matter of the keenest national concern that the South shall not be encouraged to make its colored population a vast reservoir of ignorance.” Nor did the President want all black people to become Republicans or white Southerners to remain Democrats. Instead he said, again shocking both Governor of Alabama and Mayor of Birmingham who are on the platform with him, “I want to see the time come when black men will regard themselves as FULL PARTICIPANTS in the benefits and duties of American citizenship.” This meant that they are informed and can made decisions about taxes, tariffs, foreign relations and vote as they feel best for the nation as a whole and themselves in particular. But equal education and equal access to the ballot is a necessary reality for what America means in the modern world.

Harding closes his speech by reminding Birmingham of the “magical” development of industry and progress. He said that fifty years was but a moment and if we put our hands to the plow then we can overcome any challenges facing us in the South or the nation as a whole. Yet he said the future will march on whether we march with it or not. He final words are sort of a plea to have big dreams and courage.

“the glory of your city and your country will be reflected in the happiness of a great people, greater than we dream, and grander for understanding and the courage to be in the right.”

Reflections

I grew up on Florence, Alabama. I’ve been to Birmingham many times. In fact I have been to Huntsville, Ft. Payne, Red Bay, Tuscaloosa, Gadsden, Anniston, Montgomery, Dothan, Mobile, Gulf Shores … every corner of the state. But I never knew that the President Warren G. Harding journeyed to Birmingham in October 1921 and gave the first presidential address on “civil rights.” Why is this not taught?

W. E. B. DuBois recognized the significance of what Harding had done. He also noted how Harding had qualified equality but expanded on it. He wrote,

“the sensitive may note that the President qualified these demands somewhat … and yet they stand out so clearly in his speech that he must be credited with meaning to give them their real significance. And in this the President made a braver, clearer, utterance than Theodore Roosevelt ever dared to make or than William Taft or William McKinley ever dreamed of. For this let us give him every ounce of credit he deserves.”

Now we are not claiming that Warren G. Harding was Cornel Wes, Martin Luther King Jr., bell hooks, or Amanda Gorman. But he did do something that could have been political suicide and even worse to himself. Predictably the speech exploded like a bomb in the South. The Klan excoriated Harding. Thomas Watson, Senator from Georgia ranted that Harding “had planted fatal germs in the minds of the black race.” Alabama Senator Thomas Heflin told Harding he would have to take it up with “the Almighty who has fixed the limits and boundaries” between “the races” and “no Republican can improve upon His work.” The South heard Harding in the same way DuBois had.

When I look at this trip by Harding to Alabama 101 years ago, I think of the missed opportunities. I think of the world moving on just as he said it would.

Can we imagine where we might be if the South actually did believe in equal access to the ballot. In the year of 2022, it is amazing how relevant Harding’s words are on this theme. The irony of a Republican President going into the bastion of voter intimidation and declaring essentially that democracy is a fraud without equal access to the ballot should not be lost on us.

Can we imagine where we might be if the South, and all the USA, invested in equal and real education? And not to produce more Republicans or more Democrats but to produce “full participants” in the democratic process. To fund education for a greater quality of life.

Where would we be today if our nation had responded in 1921 to this challenge by an all but forgotten President? How different the rest of the 20th century could have been. It would take another hundred years to simply ban lynching in the United States. We are still struggling with people of color as citizens. We are still struggling with anything called education.

Today we recognize Harding’s “qualification” should not have been made (for whatever reason he made them). But in his day the qualification was viewed as “smoke and mirrors.” If his agenda happened then, as Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison complained, “if the President’s theory” is carried out “that means the black man can strive to become President of the United States.”

Where are the Republicans today on civil rights? on voting rights? on education? Where is the courageous leadership on these issues?

Finally the issue has to be wrestled with, why did we not heed the call? Why did not we not dream and have courage “to do the right?” Why is it that we do not “pursue justice and justice alone” as the Holy Spirit directed us?

These are things that I reflect on when I think about the “Best Speech by the Worst President.”

Resources

Blaine A. Brownell, “Birmingham, Alabama: New South City in the 1920s,” The Journal of Southern History 38 (1972), 21-48

Charles E. Connerly, The Most Segregated City in America: City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920-1980

John W. Dean, Warren G. Harding

William B. Hixon Jr, “Moorefield Storey and the Defense of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill,” New England Quarterly 42 (March 1969), 65-81

David Pietrusza, 1920 The Year of the Six Presidents

Ryan S. Walters, Jazz Age President, Defending Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding, (full text in link) “ADDRESS OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES AT THE CELEBRATION OF THE SEMICENTENNIAL FOUNDING OF THE CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA” (26 OCTOBER 1921)

October 19th, 2022 at 5:39 pm

So much I never learned in school nor on my own. A wealth of information here in this little corner of history you visited. The potential for “good’ coming from the influence of our leaders cannot be underestimated.

You have written in the past about those who contravened against the “old” covenant, saying that it was not what was “bad” or made “obsolete”, and that it was not repealed and replaced by the new covenant, as many teach. You’ve further pointed out that biblical truth reveals the “fault” of the “old” was not the covenant itself, but rather the people who were the problem because they were unable to display fidelity to it. You have explained that the new covenant is where God himself will put his law upon our hearts so that we will show our love for him by finally being obedient to his commands.

The U.S. Constitution and its Declaration and Bill of Rights set forth words that, had the people been in fidelity to the spirit of them, could have fomented a world much better than the one we see now. The problem of “race” could have become but an isolated concern.

But…the people living under the principles espoused have fallen very short of modeling those principles. If the governments were genuinely concerned about men, its vast resources could be thrown at the problem and bring about significant, positive changes between blacks and whites, instead of creating and fomenting division for political advantage. I’m not thinking of welfare programs, legislation to “level the playing field”, or those types of things. Been there, done that. The governments could educate, advertise, teach and propagandize the moral reasons for the races to get along. Of course, I realize it’s not going to happen. Just saying…

Alas, God himself will eventually intercede in the affairs of man and Jesus will TEACH men to get along and he will rule with perfect justice.

Shalom,

JT

October 20th, 2022 at 4:40 am

Politics can never solve problems of the heart. Never has, never will. Only the “renewing of the mind” by God’s grace can do that. Perhaps politics can shape a setting where God’s Spirit is more easily proclaimed such as the Pax Romana did in the 1st Century, and we should strive for that. But politics, by its nature, is mostly about power, while Jesus is about sacrifice.

October 20th, 2022 at 8:50 am

Amen, Dan. I agree. “Renewing of the mind” is heavily accomplished from the pulpits. And I hope your comment wasn’t to imply that I was advocating politics as a solution – other than in the way that you nicely addressed it. I do believe that government can “shape” people’s minds in an appropriate context. That is, where men in the pulpit all across the land preach the whole counsel of God and government policies do not overtly and purposefully attempt to countermand and interfere with them – but instead supplement good moral virtues. I would add, when our pulpits reinforce what Dad’s in homes are (supposedly) teaching, the effect is such that it is felt in society, to include people who serve in government.

JT