Philanthropy and Racism: Paradox of John Moody McCaleb

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: American Empire, Black History, Church History, Contemporary Ethics, Discipleship, Faith, Forgiveness, J. M. McCaleb, Love, Race Relations, Restoration HistoryOf Paradox and Absurdity

Paradox is defined as “a statement that seems contradictory or absurd but is actually valid or true.” Such a definition is needed to understand much of the dynamic of race relations within the Stone-Campbell Movement. Numerous white Christians believed they had a “soft spot” in their heart for “negros” or “coloreds” as the terminology went in the day. By soft spot I mean some wealthy white believers funded various projects like purchasing tents for meetings, paid for some evangelists, and sometimes contributed money toward certain kinds of education for those among the “colored race.” Others who did not have the financial resources to enable such projects used their name or position to become a spokesperson on behalf of the African Americans. Sometimes the paradox of philanthropy and racism is thick indeed and difficult, from my perspective, to understand. Perhaps one that is symbolic of this “absurd” contradiction was, perhaps, the most famous of missionaries among Churches of Christ in his day, John Moody McCaleb (1861-1953).

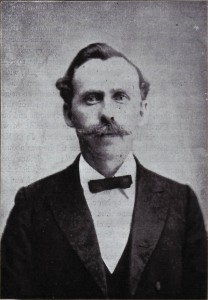

John Moody McCaleb

J. M. McCaleb was a native Tennessean born during the Civil War. He grew up on a farm in Hickman County and would love his connection with the ground the rest of his life. In 1888 he traveled to Lexington, Kentucky to study at J. W. McGarvey’s College of the Bible. As he left the College of the Bible he was opposed to both instrumental music and the missionary society and found himself more closely aligned with what would become the Churches of Christ branch of the Stone-Campbell Movement. James A. Harding was especially fond of McCaleb because of his simple trust in God and his belief in God’s special providence. Such trust was put to the test when McCaleb became became a missionary to the Land of the Rising Sun, Japan in 1892. McCaleb would remain in Japan for 34 years returning to the USA sporadically. McCaleb remained culturally a southern American in Japan, however, even importing the materials to make a southern style house that remains to this day in Tokyo. It is not my purpose to give a biographical overview of McCaleb so I recommend this extensive biographical overview of him and his work in Japan at the Boston University School of Theology’s History of Missiology page: McCaleb, John Moody: Pioneer missionary for Churches of Christ.

J. M. McCaleb’s Plan for Racial Uplift

In spite of the fact that McCaleb was thousands of miles away from not only the United States but the “heartland” of Churches of Christ, he remained amazingly connected publishing articles in many journals. He expressed opinions on most of the issues facing the Movement in his day and did so across decades. He promoted missions in Japan but also felt he could address the circumstances of our churches here in the States. In many ways McCaleb was a typical conscientious white man of his time. During the 1890s as American economic and military power began to circle the globe, white Americans felt a major burden to bring Christianity and civilization to the rest of the world. This was often done at the point of bayonet. Rudyard Kipling gave voice to this underlying angst among white Americans after the defeat of Spain in 1898 and our Christian responsibility to tame the Philippines which became part of the American Empire with Spain’s surrender. So Kipling wrote in 1899,

Take up the White Man’s burden–

Send for the best ye breed–

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

President William McKinley illustrates the sentiment when he said of the fate of the Philippines “I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen,

that I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night. And one night late it came to me this way … that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos and uplift them and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the best we could by them, as our own fellowmen for whom Christ also died.” See my blog American Empire: A Very Brief History of Our Imperialism. McCaleb had a genuine interest in souls (as the saying went). He felt this White Man’s Burden. But just how could white people help black people?

In 1904, McCaleb had read that C. P. Russell had established a “Night School for Rudimentary Instructions for Adult Negroes” in Lexington, Ky. McCaleb wrote from Tokyo in the Gospel Advocate to commend this laudable effort. “No better work could be engaged in than to establish schools for this class, not only to teach them how to read and write, but along with it give them regular instruction in the Scriptures.” McCaleb called this a “grand and glorious missionary work” that could be done in “every town and city throughout the South.” Limited education was viewed by many as a way of both helping and controlling African Americans. The right kind of education produced better servants.

McCaleb returned to the matter of education for African Americans in 1907. McCaleb was quite conscious of racism harbored by whites toward blacks. I am not sure if he was aware of his own racism but there is no doubt he participated in the myth of white men saving those who are halfway between children and devils. Something must be done to help black people. He writes in the January 1, Christian Leader and the Way,

“Race prejudice, however, stands as a great barrier to such work. If the white man makes it a custom to preach to them and mingle with them, he is severely criticised [sic] by his own people, and imposes upon himself a burden few are willing tow bear.”

This was a burden he felt himself called to shoulder. But what can be done? McCaleb notes “We accept the Turk, the Armenian, the Greek, the Japanese, the Korean, or Chinese, but not the American African.” Blacks were not allowed entrance at any of the then existing schools among Churches of Christ (there were several btw). The solution was to partner with Fisk University or the Tuskegee Institute where “the best of the African people” can receive some education. This sounds good until we read McCaleb stressing the importance of not giving the appearance of race mixing even if there were white teachers. “A white brother or brethren might do such work {teach blacks} with safety by doing it ‘professionally’ and not socially.”

Though living in a completely foreign culture, McCaleb remained a staunch segregationist. Help for “coloreds” must come but only within accepted channels. If working with Fisk University or Tuskegee could not be realized then perhaps it would be better to have special departments created within our own schools. This was indeed a forward looking notion of philanthropy mixed with the paradox of blinding racism. McCaleb argues,

“But what might be better would be to have a colored department in our own colleges, where the boys can have the benefit of our greatest and best men. But this must be done professionally, with no attempt to compromise the white people into a miscellaneous mixing with the blacks.”

Whites should treat blacks kindly, according to McCaleb, indeed we much be “fair and courteous.” But remembering one’s place in society is of utmost importance. McCaleb illustrated the importance of place by relating an event from his last visit to America. McCaleb thinks a new class of young black men not born in slavery, a “new negro.” McCaleb was riding in a coach and a young white woman was helped from the carriage by the black driver. As he did so the black man called the white woman “Bessie” as would any normal white man (we must remember that many years later Emmett Till, a 14 year old, was brutally murdered in Mississippi for supposedly similar remark in 1955). McCaleb reprimanded the black driver severely by his own testimony. He wrote,

“I believe I voice the sentiment of the brotherhood generally when I say he was out of his place. That upstartish disposition, especially among the younger negroes in which they vainly try to be white people with white people, has done much harm.”

So teaching, even by white teachers, certainly was not to change any kind of relationship between whites and blacks even in the church. Rather the black student fortunate enough to receive such a privilege was counseled to “remember his place and race, ask necessary questions, and speak courteously when he is spoken to, but carefully avoid intruding on the feelings of others. Let him seek familiar companionship with his own race.”

This is how white people can help black people according to McCaleb in 1907. Help must be given and white people must do the lifting and helping. Some education, religious and secular, but not to change the order of things. White people can never do anything that would imply equality with coloreds. This may encourage them to think of themselves as white or seek to be equal with whites. McCaleb’s most racist comment comes at this very point. Blacks hate themselves and want to be whites. He wrote, again in an article seeking to help African Americans,

“The black skin, the flattened nose, the kinky hair are hated by the blacks themselves, and every one of them would change to white people if they could. I do not blame them for this, but let us remember that this difference in race is the work of God and not of man.”

Concluding Thoughts: The Absurd Paradox … Much Yet to Do

We can say that McCaleb was a product of his time. And that would be true, for he was. He lived in a time I do not, though I have personally heard in the same sentiments spoken out loud in my presence, especially the part of how black folks want to be white. There was a surge in anti-black feeling in the late 19th and early 20th century all across the USA. The canonization of segregation by the Supreme Court. The publication of James Carroll’s 1900 book on ethnology The Negro a Beast. Worse notions were turned into nationwide best sellers by Baptist preacher Thomas Dixon Jr in The Leopard’s Spots (1901), The Clansman (1903), and The Traitor (1909) which spread the gospel of negro bestiality … these books were turned into D. W. Griffith’s “epic” film The Birth of a Nation. McCaleb knows whites are virulently racist. Yet he is conscious of the difference in how “American Africans” are treated and any number of other nationalities. Why the difference? It must be admitted that McCaleb did not approach other non-Anglo races as equals but they were not viewed quite the same as blacks. What else is operative in McCaleb’s Spiritual worldview that allows this? But the truth is McCaleb did not see himself as one of those effected by white prejudice!

But McCaleb himself felt as if, to use a modern phrase, felt he was sticking his neck out. That is he was voluntarily taking up a white man’s burden to help those he viewed as inferior than himself. He was a great example of one stepping out on faith to go to a foreign land of this there is no question. That he viewed both Japan and the rest of the world through southern culture baptized is also beyond question. He was willing to use his name to suggest that “the best” of the African race should have some form of education. He was not willing to let education, religious or “secular,” confront white racism or effect the way whites and blacks interact. Instead he was deeply opposed to such. He would praise the work of black evangelists but sought to make sure that any black man knew his place. If this is not a paradox then I do not know what one is. Sometimes “help” comes with a very steep price tag

I am eternally grateful for McCaleb’s faith and celebrate it and want to emulate it. I do not doubt that McCaleb genuinely felt some sort of burden. He is, in miniature the paradox of many. I praise the Lord for his mercy that is new every morning and his grace that is greater than our sin. I also join our Spiritual ancestor Nehemiah (1.4-11) and lament the McCaleb’s shortcomings and pray that God will help us to to recognize our own paradoxes.

Important Sources for this blog

J. M. McCaleb, “A Commendable Interest in the Education of the Negro,” Gospel Advocate (24 January 1904), 63

J. M. McCaleb, “Japan Letter: A Plea for the Colored Man,” Christian Leader and the Way 21 (1 January 1907) 2

J. M. McCaleb, “Japan Letter: How to Reach the Colored Man,” Christian Leader and the Way 21 (3 September 1907), 3

Leave a Reply