Prayer of Manasseh: The Heartbeat of Jewish Spirituality

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: Apocrypha, Bible, Church History, Grace, King James Version, Prayer, Spiritual Disciplines, WorshipThe Prayer of Manasseh is one of the most beautiful prayers ever written – even if it is in the Apocrypha. (See also my: Apocrypha: Reading Between the Testaments and Praying with Romans & Manasseh.

Prayer.

The word itself ushers us into the realms of something deeper and richer than ourselves.

Prayer.

Prayer is the witness to dynamic faith in a personal deity though transcendentally on high is deeply involved with creation.

Prayer.

Prayer is to humanity’s walk with God what hugs, kisses and sex are to a healthy, God honoring marriage.

Prayer.

Prayer is, in a way, God’s own Spirit crying out from within us in order to connect us once again with the Lover of our Souls: the Triune God.

Prayer.

Prayer connects us to the rhythm of grace and immerses us in the river of the Spirit. Is it any wonder that prayer seasons the biblical story from Genesis to Revelation?

Prayer remained an intimate part of the life of Jews in the centuries before Jesus and the early church. The Apocrypha is literally peppered with prayers. Years ago Norman B. Johnson wrote in his Prayer in the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha that nothing reveals a peoples true heart as the prayers they pray. Prayer reveals, ironically, what they believe about God … it is the unveiling of their “doctrine” of God. If this is true then the Prayer of Manasseh is the heartbeat of Jewish spirituality … a light of grace bursting forth against the darkness of evil!

Evil Incarnate – Manasseh

To understand Psalm 51 the editors of the Psalter wrote a heading for it: “A Psalm of David, when the prophet Nathan came to him, after he had gone into Bathsheba.” This great penitential psalm is gripping against the backdrop of the the whole sordid sad affair in 2 Samuel 11-2 Kings 2.

Likewise to understand the Prayer of Manasseh, and its radical claim, we must know who Manasseh was. The story of the king is told two times, in very different ways in the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 21.1-18 & 2 Chron 33.1-20). Kings, written to explain “why” Israel was “here” (exile) rather than “there” (promised land) describes Manasseh as the incarnation of evil. He even led pagan worship in human sacrifice of his own son. Manasseh’s sin almost makes David’s look, by comparison, small. He was the straw that broke the camels back. Yahweh’s long suffering patience had run out.

Chronicles, written a century or more later than Kings is written to answer the question “will God take us back? Have we sinned beyond hope?” In this narrative Manasseh is the same incarnation of evil. Yet the Chronicler does not end the story in darkness but in shocking grace. When the Evil King is blinded and taken into exile himself, Manasseh repented and prayed to the Lord. Unbelievably, Yahweh seems to have forgiven Manasseh “at the drop of a hat!” Manasseh, the greatest of all sinners, learned the truth by experience that Yahweh is “merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in hesed and faithfulness … forgiving iniquity, rebellion and sin” (See my post on the The Gracious and Compassionate God, Exodus 34).

The Chronicler does not preserve that prayer. The Prayer of Manasseh was written not only to give voice of the king’s penitent heart but to give voice to the faith of the Jewish people have in their God. The prayer reveals the God they worshiped. And what a prayer … it is one of the greatest penitential prayers ever written. It’s the heartbeat of Jewish spirituality.

Preparing to Hear Manasseh

The Prayer of Manasseh is one of the best places to camp to expose the often anti-Semitic stereotypes that followers of the Nazarene so often have of his race. This anti-Jewish bias (prejudice??) has affected not only Western Christian thought on a popular level but since the Enlightenment period has been part and parcel of Protestant biblical scholarship. Judaism was, it claimed, obsessed with ceremony and rife with legalism. Second Temple Judaism was, in this worldview, reduced to a mechanical priestly cult or rabbinic sophistry. Anything Jewish was (and often still is) dismissed outright as spiritually sterile legalism!

Anti-Semiticism perverted many otherwise brilliant scholars and colored their views on “Old Testament” studies and Judaism of the time of Jesus too. Friedrich Delitzsch even argued Jesus himself was not Jewish.[1]

So ingrained had this stereotype become that a hundred years ago it was fashionable among among biblical critics to deny the author of the Prayer of Manasseh was even a Jew rather he/she was surely a “Christian.” Though there is not a shred of evidence to sustain such a position and no one in the ancient church thought so. But as James Charlesworth has noted “the author is obviously a Jew.” Charlesworth argues that the Prayer was written sometime between 200 B.C. and 50 B.C. by a Jew that flourished in Jerusalem.[2] The light of grace shining in the Prayer exposed the bias of scholars … we need to hear it afresh even today.

There is an interesting “prehistory” of sorts to the Prayer of Manasseh. Just as Psalm 151 is preserved in the Septuagint and was discovered in the last century in its Hebrew original among the Dead Sea Scrolls so there seems to be a similar phenomena with the Prayer. The Greek version of Psalm 151 and the Hebrew are different and yet the same psalm. In Cave Four of Qumran a damaged scroll was found that contained various prayers used apparently for worship. Among those prayers was 4Q381 which reads

The prayer of Manasseh, king of Judah, when the king of Assyria imprisoned him

…. my God …. is near,

My deliverance is before your eyes ….

For the deliverance your presence brings I wait, and I shrink before you

Because of [my sins,] for You have been very [merciful]

while I have increased my guilt, and so …. from enduring joy,

but my spirit will not experience goodness for ….

You lift me up, high over the Gentile ….

though I did not remember You ….

…. I am in awe of You, and I have been cleansed of the abominations I destroyed.

I made my soul to submit to You … they increased its sin,

and plot against me to lock me up; but I have trusted in You ….

do not give me over to be tried, with You, O my God ….

they are conspiring against me, they tell lies …. to me deeds of ….[3]

The text preserved by the church has clear connections with this tradition of Manasseh’s prayer.

The Prayer of Manasseh

The Prayer as it has come down to us is a mere fifteen verses long. Read against the backdrop of the darkness of incarnate evil the Prayer is nothing short of breathtaking. This is the the New Revised Standard Version’s translation

1 O Lord Almighty,

God of our ancestors,

of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob

and of their righteous offspring;

2 you who made heaven and earth

with all their order;

3 who shackled the sea by your word of command,

who confined the deep

and sealed it with your terrible and glorious name;

4 at whom all things shudder,

and tremble before your power,

5 for your glorious splendor cannot be borne,

and the wrath of your threat to sinners is unendurable;

6 yet immeasurable and unsearchable

is your promised mercy,

7 for you are the Lord Most High,

of great compassion, long-suffering, and very merciful,

and you relent at human suffering.

O Lord, according to your great goodness

you have promised repentance and forgiveness

to those who have sinned against you,

and in the multitude of your mercies

you have appointed repentance for sinners,

so that they may be saved.

8 Therefore you, O Lord, God of the righteous,

have not appointed repentance for the righteous,

for Abraham and Isaac and Jacob, who did not sin against you,

but you have appointed repentance for me, who am a sinner.

9 For the sins I have committed are more in number

than the sand of the sea;

my transgressions are multiplied, O Lord, they are multiplied!

I am not worthy to look up and see the height of heaven

because of the multitude of my iniquities.

10 I am weighted down with many an iron fetter,

so that I am rejected because of my sins,

and I have no relief;

for I have provoked your wrath

and have done what is evil in your sight,

setting up abominations and multiplying offenses.

11 And now I bend the knee of my heart,

imploring you for your kindness.

12 I have sinned, O Lord, I have sinned,

and I acknowledge my transgressions.

13 I earnestly implore you,

forgive me, O Lord, forgive me!

Do not destroy me with my transgressions!

Do not be angry with me forever or store up evil for me;

do not condemn me to the depths of the earth.

For you, O Lord, are the God of those who repent,

14 and in me you will manifest your goodness;

for, unworthy as I am, you will save me according to your great mercy,

15 and I will praise you continually all the days of my life.

For all the host of heaven sings your praise,

and yours is the glory forever. Amen.

Listening to the Heartbeat of Second Temple Jewish Spirituality

Ben Sira surely is not far from the mark when he exhorts sinners to ”

Return unto the Lord, and forsake sins:

Make thy prayer before his face, and lessen the offense.

Turn again to the Most High, and turn away from iniquity;

And greatly hate the abominable thing” (Sirach 17.25-26, Revised Version).

Clearly in the Prayer of Manasseh, the king has turned to God and despises “the abominable thing” (I love that turn of phrase in the Revised Version).

Verses 1-4 extol the power and majesty of God in creation (God’s hesed is frequently seen in, and through, creation in the biblical psalms cf. Ps 104, Ps 136). The majesty of God is unendurable for sinners (v.5) Though God’s holiness is potentially dangerous Manasseh swiftly moves to a meditation on the “heartbeat of the Hebrew Bible” … Exodus 34.6-7 (the text thunders through the Story of Israel, See Num 14.17-18; Neh 9.16-17; Ps 86.15; Ps 148.8; Jonah 4.2; Joel 2.13; etc). In that Mt. Everest of biblical texts Yahweh reveals his true nature, his true glory in the face of Israel’s “abominable” betrayal of the Covenant of Love by declaring a Golden Calf to be their God (this is adultery on the honeymoon!).

Manasseh, like Israel of old, deserves certain death but discovers (like Job who had “heard” but now “sees”) the true nature of his God. Here is the core of what follows in the prayer:

“immeasurable and unsearchable is your promised mercy,

for you are the Lord Most High,

of great compassion, long suffering, and very merciful,

and you relent at human suffering.”

As David poured out his heart to the Lord “I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me. Against you, you alone have I sinned …” (Ps 51.3-4a) so Manasseh, incarnate evil, cries “for the sins I have committed are more in number than the sand of the sea my transgressions are multiplied, O Lord, they are multiplied!”

Like the poor tax collector (who more than slightly “echoes” the language of Manasseh!) that would not even “look up to heaven” but implored “God, be merciful to me, a sinner!” (Luke 18.13), Manasseh confesses he is unfit to even “look up and see” the height of heaven.

Here is, again in my opinion, one of the most beautiful and memorable phrases in all spiritual literature. The need for divine forgiveness and acceptance is expressed in unforgettable poetry. The Prayer says

“And now I bend the knee of my heart imploring you for your kindness.

I have sinned, O Lord, I have sinned,

and I acknowledge my transgressions.”

The penitent prayer warrior places emphasis (in the preserved Greek text anyway) upon his unworthiness. Yet the petition is simultaneously bold for the verb aniemi (aorist imperative) rendered “forgive” in v.13 means to “let go unpunished.”[4] Evil Incarnate dares to pray to go unpunished! He has no doubt of his unworthiness but he dares … dares … to pray to go unpunished! What a radical, shocking unveiling in this Jewish prayer … Manasseh believes in the infinite hesed of Yahweh which results is in astonishing grace.

Verse 14 is perhaps the climax of the prayer. It is here that the sinner, that is as dark as the blackest night, exudes a confidence in his God that is truly astonishing. So astounding those clouded by their anti-semitic glasses could not imagine a Jew praying with such confidence in God. But here it is,

“for unworthy as I am,

you WILL save me

according to your great mercy.”

The TEV captures something of the “mood” here:

“Show me all your mercy and kindness

and save me,

EVEN THOUGH I DO NOT DESERVE IT.”

This confident assurance though is in complete harmony with the Story told, sang and prayed throughout the “Old Testament.” In fact this confident assurance in the character of God is rooted in the confession, the Creed of Israel, in vv. 6-7 (Ex 34.6-7). God’s mercy, by his own testimony, is infinite.

The Prayer of Manasseh is a light of grace bursting upon the darkness. The confidence, the assurance, of the believer in the God who forgives (lets go unpunished) is the result of the light of grace.

The only response Manasseh can have to such unbelievable grace and mercy is to worship the King of Grace. “I will praise you continually all the days of my life.”

So should we!

Concluding Reflections

The great Jewish scholar Samuel Sandmel, is quoted in the Forward of David deSilva’s Introducing the Apocrypha as saying the Prayer of Manasseh “should have been ‘canonized’ within the liturgy of the Day of Atonement” (p.9). Charlesworth in fact speculates that the Prayer was indeed used in the Temple prior to its destruction in AD 70. We cannot, with the extant materials, prove Charlesworth’s speculation but we do know that the message of Prayer was treasured by ancient Christians and used during worship (and the Jews [Essenes] at Qumran). The Prayer was part of congregational worship by Christians early on. It survives Syriac, Coptic, Greek, Latin and was frequently gathered with other “prayer texts” for congregational use (called “Canticles”).

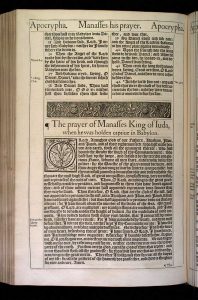

The Prayer of Manasseh has been included in the long line of English Bibles (all Medieval Bibles have it). The Geneva Bible of 1560 breaks with innovation of Martin Luther. Luther had gathered the books he called “Apocrypha” and placed them between Malachi and Matthew. The Geneva Bible separates the Prayer of Manasseh from the rest of the Apocrypha and includes it as either an appendix or last chapter to 2 Chronicles following the thousand year tradition of the Latin Vulgate. There is a marginal note that reads simply “This prayer is not in the Ebrewe, but is translated out of the Greeke.” The King James Version removed the Prayer from the end of Chronicles and placed it with the rest of the Apocrypha between the Testaments.

The Prayer of Manasseh is indeed the heartbeat of Second Temple Jewish spirituality. If this prayer reveals the author’s “doctrine of God” then that doctrine is wholesome. God is not merely a computer of justice (especially as Americans often view justice as penal). God is the gracious Father. Anyone familiar with Greek gods in the myths appreciates the huge gulf between the two conceptions of deity. From Manasseh (and many other prayers of the time) a holy but gentle even intimate quality is revealed. One never wants to get to near the gods in Greek religion.

This prayer proclaims that even the worst of sinners, incarnate evil, can find mercy, compassion and forgiveness from the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. No wonder the church got on her knees with Manasseh and prayed … and was ushered into the heart of God.

Notes:

The artwork, The Prayer of Manasseh, is by C. P. Marillier the 18th century French artist.

[1] See on a friendly and engaging level Bill T. Arnold and David B. Weisberg, “Babel und Bibel und Bias: How Anti-Semitism Distorted Friederich Delitsch’s Scholarship,” Bible Review 28 (February 2002): 32-40, 47.

[2] James H. Charlesworth, “Prayer of Manasseh” in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol 2. pp. 625-633.

[3] Translation taken from The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation, by Michael Wise, Martin Abegg Jr & Edward Cook. The translation of 4Q381 in Geza Vermes The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls reads slightly different. See also “An Qumran Fragment of the Ancient ‘Prayer of Manasseh,’ Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 108 # 1 1996, p 105-107

[4] See the Greek text of Manasseh in John R. Kohlenberger III, ed. The Parallel Apocrypha: Greek, King James Version, Douay, Knox, Today’s English Version, Revised Standard Version, New American Bible, New Jerusalem Bible (Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 1070.

July 27th, 2011 at 8:12 pm

Got this from Peggy Huffman …

“Another great blog, Bobby. Prayers in the Bible, and this one, all seem to spend much time glorifying God and His attributes and a lot of time in repentance, in comparison to the time spent asking for favors. Maybe we in the church should look to their example.”

Thank you Peggy.

July 28th, 2011 at 3:13 pm

Nowhere are we more authentically honest than in repentant prayer, for nowhere are we more transparent before God, more mindful of our earthly shortcomings, more convicted by our selfish sin, more aghast at our treatment of our Beloved, and, finally, more aware of how utterly dependent we are upon His grace and mercy.

Thank-you for “Prayer of Manasseh.” We need to remember.

Bill

July 28th, 2011 at 8:19 pm

Yeah, what Bill Morrison said – I agree wholeheartedly. Thanks for sharing this Bobby.

Hesed,

Randall