Repentance and Seasons of Refreshment … Jonah, Prayer of Manasseh, and the Psalms

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: Apocrypha, Bible, Discipleship, Forgiveness, Hebrew Bible, Jonah, Luke, Martin Luther, Prayer, Psalms, Spiritual Disciplines“That repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name” (Luke 24.47)

Caffeine Infused Thinking

I have been thinking about “repentance” recently. Or maybe it is because I recently preached on John the Baptist (and Jesus’ Outrageous Demand” of taking up a Cross!) as part of our year long journey with Jesus.

Repentance is often overlooked among modern north American disciples. Yet repentance is a prominent theme in the Hebrew Bible (sometimes given the man made name “Old Testament”). In Scripture repentance is frequently associated with Spiritual renewal, forgiveness or the remission of sin. It is no wonder that Luke’s version of the “Great Commission” records Jesus saying that “Repentance and forgiveness of sins is to be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning in Jerusalem” (Lk 24.48). Baptism is not mentioned here at all. Not knocking, or denigrating, baptism just sometimes that is all “we” tend to see. In the first Gospel sermon Peter tells the crowd that “forgiveness of sins” is connected to both repentance and baptism. It is sad that many will site this passage as proof that baptism is “unto the remission of sins” and it never occurs to them that it says the same thing about repentance. In the next chapter, Peter echoing Jesus in Luke 24, notes how repentance is again for the forgiveness of sins: “Repent, therefore, and turn to God so that your sins may be wiped out” (Acts 3.19).

The Spirit of Repentance

This spirit of repentance was deeply embedded in the Jewish psychology of the time straight from the Scriptures. Yom Kippur, day of atonement, was a day of repentance. It was a most solemn time to “come clean” before God and reorient our life and experience the joy of forgiveness. Repentance, as the key to forgiveness, runs like a thread thru the Spirit given Hebrew Bible. Three classes of texts beautifully sketch this sublime truth (and God’s sovereign freedom at the same time) in the time of Jesus: Jonah, the Prayer of Manasseh, and the Psalms (many more do too).

In Jonah, the Dove (the word “Jonah” means “dove”) angrily hisses a loveless message that we are not even sure is what God desired to be said (there is no “thus says the Lord”). Regardless, when the pagan Ninevehites heard this short message, the king proclaimed “a fast, and everyone, great and small, put on sackcloth.” Then the king (while this is happening Jonah is out sulking) proclaims “All shall turn from their evil ways and from the violence that is in their hands. Who knows!! Perhaps the Deity {the king does not know the Name of the deity} may relent …” Then the book declares, astonishingly, “When God saw what they did … God turned/changed/repented from the punishment that he had said he would bring.” In the Book of Jonah it seems like everyone repents: sailors, Ninevehites, even the animals repent! Only the tragic figure of Jonah does not seem to repent. The book closes with him stubbornly holding onto his anger at the end of the End with God pleading with him (hmmmmm echoes of a certain Parable Luke records Jesus saying). Images like this are in Luke’s mind when he speaks of repentance and forgiveness. Repentance brought about God’s infinite grace to people who did not even know his Name!

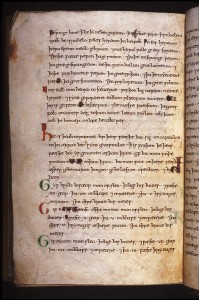

The Prayer of Manasseh, preserved in two forms one in Greek in the LXX (Septuagint) and another in Hebrew discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls, many scholars believe was part of the day of atonement liturgy in the temple (so Samuel Sandmel). It is truly one of the most hauntingly beautiful and powerful prayers in history. Scripture or not, the early church integrated the Prayer of Manasseh into its worship regularly.

The prayer warrior assumes the persona of the most wicked, and vile, king in the history of Israel, Manasseh. Jesus (as Luke shows) knows the Prayer of Manasseh as he echoes language from it in Lk 18.13, the poor sinner who would not even look up to heaven begging for mercy (cf PofM 1.9). The person confesses “the sins I have committed are more in number than the sand of the sea; my transgressions are multiplied, O Lord, they are multiplied!” If this is part Yom Kippur, then the worshipers gathered in the Temple would confess, “I am weighted down with many an iron fetter, so that I am rejected because of my sins and I have no relief for I have provoked your wrath.” And then in those immortal words, that clung to Martin Luther’s heart (Martin Luther loved the Prayer of Manasseh and believed it was Scripture at least thru the 1530s and may never have actually changed his mind on the matter) …

“And now I bend the knee of my heart, imploring you for your kindness. I have sinned, O Lord, I have sinned, and I acknowledge my transgressions. I earnestly implore you,forgive me, O Lord, forgive me! Do not destroy me with my transgression”

Then in one of the most amazing testimonies to the grace of God – like the Ninevehites – we read the confidence of faith in the God of Israel and his unchanging character as grace, mercy and love.

“For you, O Lord, are the God of those who repent,

and in me you will manifest {display} your goodness {a prototype of Paul!}

for, unworthy as I am, you will save me according to your great mercy,

and I will praise you all the days of my life”

The Penitential Psalms

The book of Psalms has seven psalms that were named the “Seven Penitential Psalms” by Cassidorus (AD 485-585?). Historic Christianity had seen the value of preserving this biblical tradition but since Cassidorus it has been customary to periodically pray these seven psalms. Jesus, Paul, Peter, the gathered early disciples in the courts of the temple, would have heard these psalms and sung them. Having a time where we stop and take stock (as in Lent or anytime) is good for our spiritual health. It is a shame that Restorationist and Evangelical traditions in North America know virtually nothing of the Seven Penitential Psalms and how they have functioned in Christian Spiritual development. Reading them together can be a powerful experience. So what are the Seven Penitential Psalms?

Psalm 6, Domine ne in furore tuo

Psalm 32, Beati quorum remissae sunt iniquitates

Psalm 38, Domine ne in furore tuo

Psalm 51, Miserere mei Deus

Psalm 102, Domine exaudi orationem meam et clamor meus ad te veniat

Psalm 130, De profundis clamavi

Psalm 143, Domine exaudi orationem meam auribus percipe obsecrationem meam

The great African Church Father, Augustine, knew this collection of psalms leading to repentance and thus grace. He instructed his church in them and perhaps we should as well.

“Out of the depths I cry to you, O LORD …

But there is forgiveness with you, so that you may be revered.” (Ps 130. 1,4)

Seasons of Refreshment from the Presence of the Lord

When Jesus tells the apostles to preach repentance and forgiveness of sins he is continuing the grace centered faith of Israel. When the nations turn to God (like Nineveh, but now we know THE name – Jesus) they will experience his gracious forgiveness. But repentance is not just for the pagans as the Prayer of Manasseh and the Psalms make clear ( … and John the Baptist). Sometimes it is God’s own people that need to radically change (repent). Repentance brings, as Peter said, “times of refreshing from the presence of the Lord” (Acts 3.20). Luke reminds us how typically Jewish was the preaching of the early followers of Jesus. Luke reminds us, repentance is not bad news at all. In fact repentance leads to amazing confidence in the amazing, infinite, unending, eternal grace of the Father of Jesus. Take the time to read Jonah, the Prayer of Manasseh and the Seven Penitential Psalms … soon. You will be glad you did.

Shalom

Leave a Reply