Uncle Tom’s Cabin, The Bible & America, #2

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: Bible, Black History, Grace, Hermeneutics, Jesus, Kingdom, Race Relations, Slavery, Uncle Tom's Cabin“Reading the Bible with the eyes of the poor is a different thing than reading the it with a full belly. If it is read in the light of the experience and hopes of the oppressed, the Bible’s revolutionary themes – promise, exodus, resurrection and spirit – come alive.” (Jurgen Moltmann, The Church in the Power of the Spirit)

An “Event”

The publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (UTC) was significant. Theodore Parker, the famous Boston preacher, called it a “world event.” And it was! Harriet Beecher Stowe had been contributing chapters of the book in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era throughout 1851-52 and the public was eating it up. When printed, the book was immediately (no international copyright laws back then) published in three Paris newspapers simultaneously. It’s first print run was sold out in a few days. The book was quickly translated into thirty-seven languages. It produced countless conversions to Christianity, such as the dying German poet Heinrich Heine. It mobilized waning anti-slavery zeal of the day.

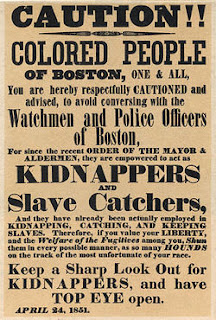

UTC was also cursed by thousands. It was banned in southern states and caused a riot among students at the University of Virgina where it was burned publicly. It was branded “pulp fiction.” Conservatives labeled Stowe a “revolutionary” and an advocate of “higher lawism” (fancy words for civil disobedience to the Fugitive Slave Law). UTC was even branded forthrightly as a “pernicious book of sin.”

Whatever one may say of the book, with one hundred and fifty years of hindsight, it cannot be said the book was neutral or conservative. Reading the book is a moral experience. I’ve never had to put Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn down (love them both) because they moved me so deeply in my inner being but I have Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Indeed I read recently from one English literature professor arguing that UTC should replace Twain in our prescribed canon of reading in high school. It has my vote.

The Bible, How is It to be Used? Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s Answer

Harriet Beecher Stowe was brilliant. She has not always been recognized as such by secular, white male, historical scholarship since WW II. Much of this scholarship has been astoundingly biblically illiterate, incredibly uniformed on how religion and American culture were intertwined through the Civil War, and even (ironically) prejudiced against her and UTC. This trend has significantly reversed in the last fifteen years most significantly with the publication of David Reynolds tour de force Mightier than the Sword: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Battle for America. Stowe read widely knowing such theological heavy weights as Schleiermacher and Feuerbach and was fans of the writers of the Romantic Movement. Her husband, Calvin, wrote her confessing how he misses their late night scholarly “discourses in sheets.” He wrote of his longing to have her with him because he,

“wants to got to bed & talk about Tholuck, Dannecker, Jean Paul, Frederick William … There is not a soul that I can say a word to about any of these matters, and I begin to find out, (what I knew very well before) that you are the most intelligent and agreeable woman in the whole circle of my acquaintance.” [1]

Among the things that disturbed Stowe was the use of the Bible by Christians to justify slavery. By 1852 there were plenty of biblical apologists for slavery and racism among United States Christians, North and South. This apparent biblical endorsement of slavery had a pacifying affect upon the anti-slavery temper that was building in the 1830s and was steadily loosing ground throughout the 1840s. For Stowe this was a serious misuse of the Word of God. Her questions generated in the narrative properly force hermenutical questions upon us too. Near the end of her book she makes a direct appeal to the reader (not the only time she does so in the book) that gives a window into what she thinks the reader should do even if some of the technical aspects of the biblical text are in question.

“But what can any individual do? Of that, every individual can judge. There is one thing that every individual can do, – they can see to tit that they feel right. An atmosphere of sympathetic influence encircles every human being; and the man or woman who feels strongly, healthily and justly, on the great interests of humanity, is a constant benefactor to the human race. See, then, to your sympathies in this matter! Are they in harmony with the sympathies of Christ? or are they swayed and perverted by the sophistries of worldly policy?”

The “sympathies of Christ.” Whatever one does about slavery, Stowe demands that the Christian side with Crucified One. This is her angle of attack against the biblical apologists of slavery and she weaves this in through her characters in the novel. I want to look at a few of these characters as they express Stowe’s criticism of the use of the Bible.

Augustine St. Clare of New Orleans: Social Location & Vested Interests

Augustine, the father of Eva, is a complex character. Augustine is married to Marie who “always made a point to be pious on Sundays.” Yet Augustine refused to attend church no matter how much his wife pleaded. Stowe tells her bigoted Christian readers that one of the greatest Christian thinkers in history was an African named Augustine “Bishop of Carthage” and that not only he but most bishops were “men of color.” Augustine St. Clare however becomes her instrument to critique not only the church but the “clergy.” The unbelieving, slave owning, Augustine does not think the Bible actually justifies slavery. When Marie and cousin Ophelia corner him on the matter he “goes off” on the ladies. Slavery is controlled by economics and the hermeneutics of the clergy is put in service of justifying oppression. I quote at length

“The short of the matter is, cousin, … on this abstract question of slavery there can, as I think, be but one opinion. Planters who have money to make by it, – clergymen, who have planters to please, – politicians, who want to rule by it, – may warp and bend language and ethics to a degree that shall astonish the world at their ingenuity; they can press nature and the Bible, and nobody knows what else into the service …”

But should slavery adversely affect the price of cotton, Augustine says

“Well suppose that something should bring down the price of cotton once and forever, and make the whole slave property a drug in the market, don’t you think we should soon have another version of the Scripture doctrine? What a flood of light would pour into the church, all at once, and how immediately it would be discovered that everything in the Bible and reason went the other way!”

Stowe, through Augustine, pins the vested interest that drives the justification of slavery. The real motivation was not exegesis and certainly not the “sympathies of Christ” but power and economic interest.

“If I was to say anything on this slavery matter, I would say out, fair and square, ‘We’re in for it; we’ve got’em, and we mean to keep’em, – it’s for our convenience and our interest;’ for that’s the long and short of it,’ that’s just what the whole of what ll this sanctified stuff amounts to, after all; and I think that will be intelligible to everybody, everywhere.“[2]

Looking back it is easy to see that Augustine (Stowe) was dead on in this critique. In the Stone-Campbell Movement one who defended slavery was James Shannon. Shannon was ne of the most educated men of the movement. He was president of Bacon College (the first college in the SCM) and later the University of Missouri. In 1844 he addressed the student body of Bacon College on The Philosophy of Slavery, As Identified with the Philosophy of Human Happiness. This was later published in a booklet in 1849 and went through several editions. Shannon offered a myriad of interpretations in support of slavery as essential to “human happiness.” In his criticism of the abolition movement he freely uses the economic dimension. Abolitionists were guilty of breaking the tenth commandment “thou shalt not covet.” “Hence, the advocates of Emancipation without compensation to the owners, are involved in the deep guilt … of violating the tenth commandment and exciting others to a similar violation.” [3] Slave holders are entitled to their “property” regardless of any claim by abolitionists. Stowe sees this argument for what it is … vested interest and power play … but Shannon would have denied that. Are we blind to our own vested interest and how that shapes our hermeneutic?

George Harris, Eliza’s Husband: Spirit of Humanity & Fellowship

George is a powerful character we even meet him before Tom in the narrative. He is intelligent (taught himself to read). He is creative. He is militant. His was separated from his wife, Eliza, and baby son. He and Eliza’s exodus to the north is the opposite mirror for Tom’s descent further south. Doubt plays a significant role in his character. Stowe believed that God, especially through Christ, was on the side of the sufferer. She described him as “God the Omnipotent, the Creator, the Destroyer, is suffering himself to be detained in weak human hands, and controlled by the passionate earnestness of human desire … He whose touch could annihilate, can yet be held by your infant hand–can be swayed by your prayer.”

It is this suffering, caring Creator, that is so difficult for the oppressed slave – in George – has difficulty in believing. During the journey George meets Mr. Wilson a law and order man. Mr. Wilson attempts to use the Bible to support the Fugitive Slave telling George it is his Christian duty to return. He told him how Paul sent Onesimus back to Philemon. Yet the angry fugitive will have none of it.

“Don’t quote the Bible at me that way, Mr. Wilson, … don’t! for my wife is a Christian, and I mean to be, if I ever get to where I can; but to quote Bible to a fellow in my circumstances, is enouch to make him give it up altogether. I appeal to God Almighty; – I’m willing to go with the case to Him, and ask Him if I do wrong to seek my freedom.”

Mr. Wilson admonishes George to trust in God and his laws (which in this case would mean obedience to the Fugitive Slave Law). But George fires back at his antagonist: “IS there a God to trust in? … There’s a God for you, but is there any for us? [i.e. black slaves]”

George is reunited with his beloved wife (not legally married because they are slaves) and his son Harry in a Quaker community in Ohio. The Quaker’s were on the outside of the orthodox religious establishment in America so these folks have a similar function as the non-believing Augustine. Through these unrepentant breakers of the Fugitive Slave Law George learns the true meaning of Christian faith. Stretching all social bounds of the time, Stowe has George and Eliza sit down and eat at white person’s table … in a white person’s home. As Jesus affirmed the human worth and dignity of social outcasts in the Gospels so George is moved deeply that a person accords him actual human dignity. The Quaker Simeon Halliday tells George that God actually bestows upon us goods for the purpose of being generous and merciful. George is astonished that this man would risk going to jail to help him and his escaping family. Simeon and George read Psalm 73 together and it soothes his soul and the flame of faith begins to flicker in George. Stowe says of this psalm that the words might sound like pious bosh from a self-indulgent exhorter but “coming from one who daily and calmly risked fine and imprisonment for the cause of God and man, they had a weight that could not but be felt …” Simeon demonstrated the sympathies of Christ. George rejected the use of the Bible as a prop for injustice. At the Table we are all equal …

Uncle Tom: The Man of Sorrows

One of the “ah ha” moments for the followers of stereotypes is that Tom, as Stowe narrates him, was anything but an “Uncle Tom.” He is introduced to us a “large, broad chested, powerfully made man.” The “air” around him is “self-respecting and dignified.” He is literate (it was against the law in many southern states for a slave to learn to read). Tom is strong and stands his ground. He sacrifices his personal needs for the sake of other slaves and refuses to disobey his conscience. He is a principled man … a serious stab at the ugly stereotypes of black men of the day. He will not cooperate with evil and will not bring harm to others.

Tom is truly a Christ figure in the book. Tom is the ultimate embodiment of the true meaning of the Christian faith and the Bible in particular. As Tom is ripped from his wife (not a legal marriage again), sold down river to almost certain death we hear the pathos of the slaves come through with power in Stowe’s imagery. The Mississippi is imagined to be the river carrying the lamentations of the slaves to the – absent – God. Would that “the tears of the oppressed, the sighs of the helpless, the bitter prayers of poor, ignorant hearts to an unknown God – unknown, unseen and silent, but who will yet ‘come out of his place to save all the poor of the earth!”

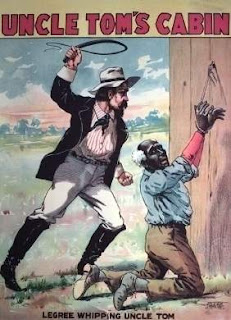

Tom arrives at his new “owner,” Simon Legree. Legree is Tom’s third owner in the narrative, each spans the kind of slave owners Stowe believed to be in the South. It is easy to hate Legree. Legree is an inhumane tyrant. But Stowe does not want us to hate Legree rather she invites us to pity him. He is the end result of the system of dehumanization of slavery upon the slave holders! He pales in comparison to Tom. He retains the brute power of force but is emasculated by the real power of Tom’s presence. The more Simon rails at, and abuses, Tom the truth of what he is is revealed. Tom reads the Bible to the other slaves on Legree’s plantation. An important text was Matthew 11.28, “Come unto Me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” But the slaves cannot believe that God “is around” for “God never visits these parts.” Stowe quote Ecclesiastes 4.1-2 to embody the darkness of Legree’s place.

“Again I saw all the oppressions that are practiced under the sun. Look, the tears of the oppressed–with no one to comfort them. And I thought the dead, who have already died, more fortunate than the living, who are still alive …” (NRSV)

Cassy, Legree’s sex slave, laments to Tom – the Lord “isn’t here! there’s nothing here, but sin and long, long despair!” Truly Tom has arrived in hell.

To Legree Tom was a trouble maker precisely because he was such a powerful man. “Had not this man braved him, – steadily, powerfully, resistlessly, [sic]- ever since he bought him.” This made Legree fear and hate Tom. Legree attacks Tom’s faith saying “I’m your church now!” Legree succumbs to the irrational fear of the oppressor (echoes of Exodus 1.12) in his fear of Tom’s mighty personality. When Tom refuses to flog another slave Simon he has Tom whipped nearly to death. After the whipping Tom says to Simon,

“I’ll give ye all the work of my hands, all my time, all my strength; but my soul I won’t give up to mortal man. I will hold to the Lord and put his commands before all, – die or live; you may be sure on’t. Mas’r Legree, I an’t a grain afeard to die. I’d soon as die as not. Ye may whip me, starve me, burn me, – it’ll only send me sooner where I want to go.”

Sambo and Quimbo, slave overseers bought off with alcohol and sexual favors, finish the cruel torture of Tom. Yet in the book Tom forgives them and they break down: ‘O, Tom! do tell us who is JESUS, anyhow?” Sambo and Quimbo are victims of the system of evil too. Tom’s forgiveness simply enrages Legree. His anger boils as he realizes that “his power over his bond thrall was gone.” Simon Legree literally beats Tom to death in an incredibly moving narrative.

Tom is the Christ who willingly endures great suffering for others. As Tom nears death he reads of the Passion of Jesus. Soon “a vision rose before him of One crowned with thorns, buffeted and bleeding.” Like Jesus he forgives his enemies and loves them. Tom is the embodiment of the sympathies of Christ.

Far from being an “Uncle Tom” the Tom that Stowe narrates was incredibly challenging and offensive to white Christians of her day. And he is still a powerful figure when read today. Tom is the model of nonviolent resistance found in Martin Luther King Jr and Rosa Parks. Just how threatening Tom was we will see in our next blog.

In Worship at the Lord’s Table

Harriet Beecher Stowe believed that God had moved her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. While there were antecedents in her life for the contents of the book it was not until February 1851 that she began the novel. While visiting Brunswick, Maine she attended the First Parish Church. As she was taking the bread and wine she reflected upon the cross of Jesus. She says that she at that moment had a “vision that was blown into my mind as by the rushing of a mighty wind.” The vision given her at the Lord’s Table was of an old slave being whipped to death by two fellow slaves who were under the control of a white man. Stowe was so disturbed by her vision that she began to write UTC and felt the entire time as if the words were from another source. The story of Tom’s death in the novel is clearly the literary version of her vision. For her a visit to Calvary at the Table led her to another Calvary … not the one of Christ but an American Calvary of slavery. At the Table, in worship, she was moved to identify powerfully with the hated and oppressed nobodies in the United States … the slaves. Worship changes lives – just ask Harriet.

Final Hermeneutical Thoughts

Stowe saw powerfully and clearly that God takes a side. Her frustration with the church and Christians in general because of their complicity in injustice reached a breaking point. We have only scratched the surface of how she explores biblical themes and how they might look in the eyes of the oppressed. Through her novel she forces us to ask potent questions. Is it a legitimate reading of Scripture that endorses something blatantly contrary to the values and mission of Christ? She forces us to ask of ourselves … are we so enmeshed in the machinery that our exegesis and theology always supports us in our own agenda? She forces us to ask does the fact that we have money or power control how we read the Bible and determine what is or is not righteousness? Again she saw that God does takes sides. She saw this because she looked through the eyes of the slave. Reading from that location is not always easy.

One powerful narrative that slaves in the South routinely gravitated to was that of the Exodus. There interest in the Exodus was not historical or critical but it was gripping. They saw something that whites like James Shannon did not … God took sides. If we look briefly at the Exodus we see four things that are theologically significant and call for response by God’s People:

1) A struggle between the powerful and the weak is going on

2) God hears the cries of the weak and is fully aware of the situation of the weak

3) God is not neutral in this struggle between the powerful and the weak

4) God calls his people to join in the struggle for the weak [4]

If this actually true then how should that affect our Bible reading? and more importantly our living in this world? Harriet Beecher Stowe believed it meant shelving self-interest and engage in the risky business of altering the status quo … I think we can learn a lot from this small but powerful lady.

NOTES:

1] Quoted in Patricia R. Hill, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a Religious Text,” a paper delivered at the June 2007 Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the Web of Culture conference sponsored by the National Endowment of the Humanities. Pages are not numbered but on my print copy see p. 4.

2] All quotes from The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin, eds Henry Louis Gates Jr & Hollis Robbins (W. W. Norton, 2006).

3] James Shannon, The Philosophy of Slavery, As Identified with the Philosophy of Human Happiness, An Essay (A. G. Hodges & Co., 1849), 13.

4] For a very readable source on hearing the Bible from another location, and that looks at specific texts and works through them see Robert McAfee Brown Unexpected News: Reading the Bible with Third World Eyes (Westminster/John Knox 1984). See pp. 33-48 on listening to the Exodus.

February 5th, 2013 at 6:38 pm

Thanks again Bobby. I appreciate your efforts and for sharing with us.

Hesed,

Randall