Ancestry of the King James Version #3: Making Books in the Ancient World

Author: Bobby Valentine | Filed under: Bible, Church History, Exegesis, Jeremiah, King James VersionSee my previous Ancestry of the KJV #1 and Ancestry of the KJV #2

The Beginnings …

Long, long before there was a bound volume of collected works that have come to be called “The Bible,” the works of Scripture had to be go through a process of production. A text has to be written down. How did this happen? In this blog we will examine very briefly how a “book” was actually made for centuries and centuries before there was such a thing with a spine and pages bound together. This is important information for all believers and is the beginning of the story of the Ancestry of the English Bible.

When the Lord God called Moses to lead a band of slaves out of the horrors of Egyptian slavery he, an 80 yr old man, would change human history. Up until Moses there had been no Bible of any kind. Moses would become the first great prophet of Yahweh’s good news. Tradition has it that Moses was the first great author of the Pentateuch but whether or not he wrote it all need not detain us. He did write and that is the beginning of “enscripturation.” Moses did not go one night to Kinko’s to have Genesis or Deuteronomy copied on a xerox machine. He likely did not have the opportunity to visit Wal-Mart to buy spiral bound college ruled notebooks either. The making of a book in the Ancient Near East was a far different process than today.

The most likely surface for Moses to have written on was clay tablets or possibly stone. The Ten Words (commandments) were so written (Ex 32.19; 34.4). Paper as we know it did not exist. Papyrus was used to make a paper “like” sheet but was very fragile. Most important documents were inscribed on clay tablets. Like this example of one of the Amarna Letters uncovered from Akhenaton’s capital city dating to about 1400 B.C.

Thus a “book” in Moses’ day did not have pages rather it had tablets with writing on both sides. A good example of this would be the Enuma Elish, a Babylonian story with affinities to the story in Genesis, is recorded on 6 or 7 tablets.

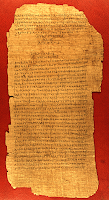

Much later in history scrolls became common. Though not as durable as clay tablets they were used throughout the Mediterranean basin. Scrolls were, and still are, made mostly of leather. Hide would be dried and smoothed out to make Vellum. Writing would be done on the inside so the writing would be protected. Scrolls could become bulky. For example a the Gospel of Luke would be about 34 feet long. The Isaiah scroll among the Dead Sea Scrolls is over 30 feet long. Knowing this helps us have greater appreciation for the story in Luke 4 where the scroll was handed to Jesus and he turned “to the place where it was written” (referring to Isa 61 cited in Lk 4.17). The Temple Scroll, another treasure from Qumran, is 28 feet long. Here is the famous Isaiah scroll …

The epistles in the New Testament were most likely written on papyrus instead of leather. Here is a picture of p75.

But “how” did the biblical writers go about writing their books? What can we know about their craft? Did they just one day sit down and write, say, 1 Kings, or Psalms or the Gospel of Luke? Did they collect data (do research?) Or were they simply a supernatural word processor that God downloaded a PDF file? The Bible does not answer all these questions directly, however it does provide some remarkable insight into some of these matters.

Here is an exercise for you: Compare Isaiah 36. 1, 4, 11f with 2 Kings 18.13,19ff, 26ff. Note how 2 Kings 18.13-20 is reproduced in Isaiah 36-39.

Jeremiah as our Laboratory

The Book of Jeremiah is one biblical book that makes it clear that it was not composed all at the same time. Indeed this book was written over a period of no less than 18 years and perhaps much longer. The text of the Book tells us that our present book is actually made up of three books that have probably been brought together by Baruch. We are told about the writing down of Jeremiah’s oracles in the following manner:

“In the fourth year of Jehoiakim son of Josiah king of Judah, this word came to Jeremiah from the LORD: Take a scroll and write on it all the words I have spoken to you concerning Israel, Judah, and all the nations” (36.1-2).

This command came to Jeremiah in the fourth year of Jehoiakim’s reign or in 605 B.C. By this time Jeremiah had been preaching for 22 years. If we take this command seriously, and I see no reason to doubt its veracity, then prior to this time Jeremiah had not published his oracles in his Jeremiah sermon book! This scroll that Jeremiah had copied out was destroyed by that Judean king and was burned a sliver at a time in the fire (Jer 36.22-23).

Thus the “first edition” of Jeremiah suffered a fate similar that William Tyndale’s early efforts would suffer … pyromaniacs got a hold of it. Jeremiah was instructed to make a second edition (36.27-29). So the prophet called upon the services of his scribe Baruch. The Bible says that Jeremiah called “Baruch son of Neriah, and Baruch wrote upon a scroll at the dictation of Jeremiah all the words of the LORD which he had spoken to him” (36.4).

This rewritten scroll was the beginning of our present canonical Jeremiah. This scroll did not contain all our present book of Jeremiah for the prophet ministered for another 18 years after this scroll was written … The ministry of Jeremiah lasted at least till 586 BC. This scroll probably consisted of chapters 1-25 of our Book. In 25.13 we read, “I will bring upon that land all the words which I have uttered against it, everything written in THIS book, which Jeremiah prophesied against the nations.” What makes this statement significant is the reference to “this book” and “this book” is given the same date of the fourth year of Jehoiakim’s reign (25.1). So the first stage of making our Book of Jeremiah took place around 605 B.C. when Baruch wrote down Jeremiah’s early sermons.

The Second Book begins with 46.1 which also referred to a “book” in the Hebrew text. This is a collection of oracles against the nations from chapters 46-51. This second book ends with the words “The words of Jeremiah end here” (51.64b).

The Third component in our canonical Book is called the “Book of Consolation.” It is called such because in it God assures Judah of his grace and the promise of restoration following the Exile. We read in the text “This is what the LORD, the God of Israel, says: Write in a book all the words I have spoken to you” (30.2). Jeremiah’s Book of Consolation is written near the END of the prophet’s ministry because it is written AFTER the fall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. (which is presupposed in the text, 30.18-21; 31.23-28).

What can we conclude from these seams in the Book of Jeremiah? There were three books:

1) chapters 1-25;

2) chapters 30-31;

3) chapters 46-51.

The remaining material in our present Book of Jeremiah consists of chapters 26-29; 32-45; and 52. What is significant about this material in chapters 26-29, 32-45 and 52 is in narrative prose and written almost exclusively in the third person. The material in the other chapters is poetry and oracle in nature. Chapter 52 is almost verbatim 2 Kings 24-25.

It is not hard to imagine that Baruch, Jeremiah’s loyal scribe, took these three works and put them together and added the narrative portions about Jeremiah (not just what Jeremiah said). This is how, it appears to me, that at least one book of our Bible was made.

Biblical Writers Use of Research in Composing their Works

Earlier we asked if biblical authors used resources or did “research” in their writing. We have learned from the Book of Jeremiah that our present book clearly went through stages or editions before it came to be what we have today. Other writers went through a process as well. The books in the Hebrew Bible we call Chronicles, Ezra & Nehemiah and Joshuah-2 Kings (one long work) make frequent use of an ancient version of MLA.

I will focus on Chronicles briefly as an example. The Chronicler is deeply interested in the Temple and seeks an answer to the question (answered throughout his writing): “Will God take us back? Will God dwell with us again?” As he writes his history in search of an answer to that question he peppers his material with “footnotes.” The following is probably an incomplete list of works he used in his research:

1) The annals of King David (1 C 27.24)

2) The Book of the Kings of Israel and Judah (2 C 27.7; 35.27; 36.8)

3) The Book of the Kings of Judah and Israel (2 C 16.11; 25.26; 28.26; 32.32)

4) The Book of the Kings (2 C 9.1; 2 C 24.27)

5) The Decree of David the King of Israel and the Decree of Solomon his Son (2 C 35.4)

6) The Annotations of the Book of the Kings (2 C 24.27)

7) The Records of Nathan the prophet, the Records of Gad the Seer (1 C29.29; 2 C 9.29)

8) The prophecy of Ahijah the Shilonite (2 C 9.29)

9) The Visions of Iddo the Seer (2 C 9.29)

10) The history of Uzziah which Isaiah the prophet, the son of Amoz has written down (2 C 26.22)

It seems fairly obvious that the Chronicler did quite a bit of research in his effort to communicate a message sorely needed in 400 B.C. Yes, Yahweh will take us back in his infinite Hesed/grace! Research was not limited to the Hebrew Scriptures alone as the above list makes explicit. In the New Testament, Luke makes it quite clear that he was a diligent student claiming,

“Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first to write an orderly account …” (1.1-3).

Luke indicates he conducted interviews, collected and evaluated written sources (he clearly knows of other written sources) much like the Chronicler had done long before him.

In this post we have looked at the process, as best we can, of how some of the books of the Bible were made. Inspiration included this phenomena. Over a period of time all these books that were made were gathered together to form our present Book of Books … the Bible.

P.S.

The “editions” of Jeremiah continued after what became our canonical book in the Hebrew text. The Septuagint (LXX) edition of Jeremiah (the Greek translation) is nearly 3000 words shorter than the Hebrew version. And in the LXX the “Epistle of Jeremiah” was often appended to the Book itself. For a nontechnical, and fascinating, introduction to these matters I recommend Steve Delamarter’s “But Who Gets the Last Word: Thus Far the Words of Jeremiah” in Bible Review (October 1999): 34-45

January 4th, 2011 at 2:08 pm

Ah, but which version of Jeremiah came first?

The Septuagint version or the Hebrew?

As a larger question, why has Christendom essentially defaulted to the Jewish position regarding the Hebrew Scriptures rather than the position of the early church?

After the death of Jesus, who had better knowledge or a final “say” about books like Baruch, Tobit, etc?

January 4th, 2011 at 2:14 pm

Bobby,

Another example I have used for how inspiration may have worked is the four references of the Titulus Crucis. Matthew 27 quotes the sign as reading, “THIS IS JESUS, THE KING OF THE JEWS”; Mark 15 says, “THE KING OF THE JEWS”; Luke 23 has the sign as , “THIS IS THE KING OF THE JEWS”; and John 19 reads, “JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS”. All four “remembered” the titulus reading something slightly different from each other, while clearly the sign could have only read one way. This appears to discount some sort of “holy PDF download”. Thanks for the review!

January 4th, 2011 at 3:44 pm

Anon …

That is a good question. Clearly the Hebrew Jeremiah was the first. But that really does not settle the question though because the Masoretic text may have been a revision of some earlier text. Among the Dead Sea scrolls it is clear that more than one “text type” was known to them. Among some of the works there the Masoretic text is very close but others there are significant variations … and the LXX is a translation of SOME Hebrew text.

January 4th, 2011 at 6:20 pm

What about the last two questions from Anon, Bobby?

January 5th, 2011 at 12:30 am

Anon,

Do I know you?? This isn’t a case of bait and switch I hope. The question has little to do with my post.

But at any rate I’m not sure what you are seeking. Are interested in the textual history of works like Tobit and Baruch or are you interested in the canonicity and the associated debates regarding these works?

These ancient Deuterocanonical bks would have a similar textual history as any other ancient work (Jeremiah for example). Tobit existed in the Hebrew as evidenced by the Dead Sea Scrolls. It was translated into Greek at some point prior to the Christian era and was regarded as scripture by some Jews and many Christians.

After the Christian age these books, like the rest of the LXX, was associated with the church and fell into disuse. So the Christians largely preserved this and the other works which are denominated Apocrypha now.

January 5th, 2011 at 4:04 pm

No bait and switch, but a plain question I have struggled with myself.

Why has Christendom essentially defaulted to the Jewish position regarding the Hebrew Scriptures rather than the position of the early church?

Who says the Jewish people were better able to indicate the “real” books from God than the early Christians, especially since the writings in the apocrypha were quoted and used by so many of them?

I can certainly see how these books would have fallen into disuse by the Jewish people after the start of the Christian age. I’m just not sure how / why the reformers were in a better position to indicate the canon than Clement, Tertullian, Origen, etc.

If the Spirit were “guiding” the early Christians such that the proper decisions were made about the books in the NT canon (which is a very common explanation), why have we defaulted to the Jewish decision rather than to those same early Christians with regard to the Hebrew Scriptures?

I’m just confused and don’t mean to cause any grief here.

January 5th, 2011 at 5:44 pm

Anon,

You have done nothing wrong so you have no reason to apologize.

The exact limits of the canon of the First Testament is a sticky matter. There is no debate about the Torah or even the prophets. In that last section of the Hebrew canon known as the Writings however there are some fuzzy areas and it does not do any of us any good to deny this.

People sometimes speak of the “Jewish” canon. But what they really mean is the rabbinic canon. The Jews of Jesus’ day were not of one mind regarding the extent of the canon: the Sadducees & Samaritans held to only the Torah; the Pharisees included the prophets & writings (but the exact limits of those writings is the debate); and the Qumran community seems to have included other works in their holy writings. The critical period following the destruction of the temple were critical for what became Judaism.

The early church’s initial canon of the First Testament formed BEFORE the destruction of the temple. The books in what Protestants term “Apocrypha” were not all valued equally in the early church or among Jews. Some like Wisdom and Sirach were rich indeed.

In the final analysis we must recognize what even the very conservative historian, Everett Ferguson, has pointed out:

“No common agreement was reached on these additional books to count as canonical and indeed it was not until the age of the Reformation, when Protestants insisted on limiting the Old Testament to the thirty nine books accepted by the Jews, that the Roman Catholic church made an official determination of which books …”

Even among those scholar of the early church who were aware of the Jewish counting, like Athanasius and in THEORY made a distinction between the Hebrew canon and the Apocrypha actually cited and used those books as Scripture. Ferguson says of Athanasius, “In practice he quoted these books, especially the Wisdom of Solomon, witout distinction from the canonical books.” (Church History, Vol 1, p. 113).

Oskar Skarsaune in his outstanding work, In the Shadow of the Temple: Jewish Influence on Early Christianity, points out that there were in essence two canons of the “Old Testament” in the early church. One he calls the “learned” canon that was more theoretical than anything. The other he called the “folkish” canon which is what the vast majority of the church used in worship and study. This canon was the basic contents of the LXX and the Old Latin (see his discussion on pages 279-293).

I do not want to disconnect the church from its Hebraic roots. But those roots INCLUDE the LXX and the Apocrypha.

Anon it is not the case that the classic “Protestant” position is the same as that in modern American Evangelicalism. Luther, for example, rejected the canonicity of the Apocryphal books but he went through the trouble of translating them and including them in his Bible. William Tyndale who never completed the Bible (did the Pentateuch & Jonah of the “OT”) but in his NT translation he included “lectionary readings” (daily prescribed readings) from Sirach and Wisdom. The Geneva Bible is as Protestant as they come and it included the Apocrypha and even had the Prayer of Manasseh following 2 Chronicles. The King James Version includes the Apocrypha as did the Revised Version and the RSV and most other major translations.

We should know these books.

January 6th, 2011 at 6:50 pm

Is there a single book that you might reccomend as an entry level to the “non-canonical” books that should be part of one’s vocabulary?? If not one, perhaps a listing of the books?

January 6th, 2011 at 6:52 pm

Any chance that you could post a list of books that a beginner could start with ?? Some of us got raised with the admonition to avoid non-canonical books at all cost..:)

January 6th, 2011 at 7:21 pm

Price,

The works that are under consideration here are those that were part of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible dating to about 300ish to 150ish BC). These works are commonly termed “The Apocrypha” in Protestant lingo and Deuterocanonical in Roman Catholic lingo and simply Scripture by the Greek Orthodox and Coptic Churches.

I would recommend getting the NRSV with Apocrypha as your entry into these works. The NRSV is an outstanding translation of the entire biblical corpus. The following works will appear in the NRSV

Tobit

Judith

The Greek Esther

Wisdom of Solomon

Sirach

Letter of Jeremiah

Three Additions to Daniel

1)Prayer of Azariah & Song of 3 Jews

2)Susanna

3)Bel & the Dragon

1-4 Maccabees

1-2 Esdras

The Prayer of Manasseh

Psalm 151

Not all of these works are of equal importance … just as all in the “canonical scriptures” are not. Second Peter is hardly as important or rich as the Gospel of John. Obadiah is hardly as rich as Isaiah. Second Esdras is not as rich as Wisdom of Solomon. But you will be blessed and once you read them you will wonder why you hadnt before. Here are a couple of links on my blog to works in the Apocrypha:

Judith: God Saves Through A Woman

http://stoned-campbelldisciple.blogspot.com/2007/08/legendary-women-on-family-tree-judith.html

Susanna: Legendary Woman on the family Tree

http://stoned-campbelldisciple.blogspot.com/2007/08/legendary-women-on-family-tree-susanna.html

Romans & The Prayer of Manasseh

http://stoned-campbelldisciple.blogspot.com/2006/06/praying-with-romans-and-manasseh.html

Shalom,

Bobby V